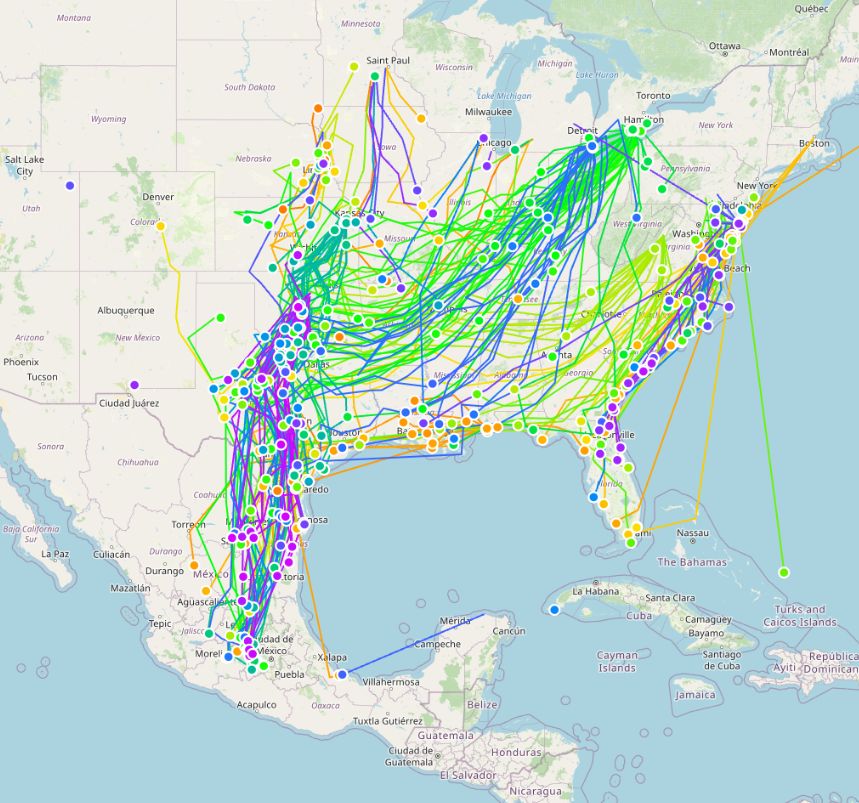

Like many in the monarch community, I have been fascinated by the data coming in from the Cellular Tracking Technologies (CTT) BlūMorpho tags. In particular, this image that has been making the rounds on social media has captured (maybe too much of) my attention:

Monarch tracks from 2025 season. Credit CTT

Each one of those lines is the path of an individual monarch butterfly during the southern fall migration. For those who are not initiated, the CTT tags are tiny bluetooth devices that emit a unique signal when in sunlight. Any cellphone within range that hears this signal can then report that detection back to their database. It works the same way as AirTags do, except we are tracking butterflies instead. The New York Times did a story on this project recently, which is excellent if you want to learn more.

We Can Now Track Individual Monarch Butterflies. It’s a Revelation. — The New York Times

BlūMorpho tag on monarch

When I looked at the map of all the different tracks, I couldn’t help but wonder why the butterflies would wander generally southwest, then turn abruptly south around the panhandle of Texas. Those north of the turning point also showed no SW movement at all, but instead flew straight south to meet the rest of the butterflies. There’s even a few that flew east to meet at this particular location where all the butterflies seem to know “this is where we head south.” It is mysterious, but I thought surely, there must be some physical feature in the environment that the butterflies are responding to.

I have a background in GIS and so started to explore different climate datasets that might explain why the butterfly movement patterns change so suddenly in an otherwise flat region of North America. I’ll spare you all the variables I explored and get straight to the best one I found: Actual Evapotranspiration

Actual Evapotranspiration (AET) is a measure of how much water is cycling in the environment through evaporation from the earth and transpiration from plants. It’s a proxy for water availability in the landscape. High AET areas are more humid and have more vegetation. Low AET areas are closer to deserts.

Now monarchs are not plants, of course, but are subject to similar constraints. They are vulnerable to desiccation (drying out) and need frequent nectar stops for their journey south. So, it makes sense then that they would want to avoid especially arid places that threaten too much water loss during their migration. Flowering plants with lots of watery nectar are also rare in these places. So, what happens when we overlay a map of monarch movement over this measure of water loss?

AET and monarch movement

In the figure above, I’m showing a 10 year average of the migration months (Sept-Nov) of AET in North America. Green areas indicate places where water is relatively abundant, like much of eastern US. Brown areas are the opposite, where water is at a deficit. I was shocked with how well this measurement mapped onto the movement of the butterflies. Indeed, it seems they are moving SW until it gets a little too dry, and then continue south, like following a wall. Those north of this boundary might also want to move SW, but are unable to do so unless they risk entering more arid parts of the country. Even that one butterfly that flew southeast can be explained by following a gradient of higher AET values.

The same constraints on movement appear to be true for large bodies of water. Butterflies that are tagged at lower latitudes will swing southwest like the rest, but then will skirt along the Gulf Coast, then head predominately West. Around Texas, the boundary between humid and dry meets with the Gulf, and you get what I presume is the “Texas Funnel” I have heard other monarch biologists discuss.

I’m still perplexed about the butterflies crossing the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. How do the butterflies know to “stop” at their overwintering grounds? My little visualization here doesn’t help solve that mystery.

I’ve always heard that the Rocky Mountains separate the Eastern and Western Populations, with the assumption that the physical topography was too great to pass over. Perhaps it is the arid part of the Great Plains instead? It makes me wonder about all the monarchs passing through Arizona, however. Maybe they represent some small percentage that aren’t operating with the same navigational program.

Exciting times in the monarch world. Looking forward to what other researchers find with this rich new source of information.